| |

Jack London's Description of the

View from Sonoma Mountain

Editor's note: In the early

years of this century, writer Jack London owned and lived

on a ranch near Glen Ellen which extended to the top of

Sonoma Mountain. Much of this ranch now makes up Jack

London State Historic Park. The "southern

edge of the peak" mentioned in this excerpt would be

at or very near Lafferty's upper meadow. Editor's note: In the early

years of this century, writer Jack London owned and lived

on a ranch near Glen Ellen which extended to the top of

Sonoma Mountain. Much of this ranch now makes up Jack

London State Historic Park. The "southern

edge of the peak" mentioned in this excerpt would be

at or very near Lafferty's upper meadow.

There were no houses

in the summit of Sonoma Mountain, and, all alone

under the azure California sky, he reined in on the

southern edge of the peak. He saw open pasture

country, intersected with wooded canons, descending

to the south and west from his feet, crease on crease

and roll on roll, from lower level to lower level, to

the floor of Petaluma Valley, flat as a billiard-table,

a cardboard affair, all patches and squares of

geometrical regularity where the fat freeholds were

farmed. Beyond, to the west, rose range on range of

mountains cuddling purple mists of atmosphere in

their valleys; and still beyond, over the last range

of all, he saw the silver sheen of the Pacific.

Swinging his horse, he surveyed the west and north,

from Santa Rosa to St. Helena, and on to the east,

across Sonoma to the chaparral-covered range that

shut off the view of Napa Valley. Here, part way up

the eastern wall of Sonoma Valley, in range of a line

intersecting the little village of Glen Ellen, he

made out a scar upon a hillside. His first thought

was that it was the dump of a mine tunnel, but

remembering that he was not in gold-bearing country,

he dismissed the scar from his mind and continued the

circle of his survey to the southeast, where, across

the waters of San Pablo Bay, he could see, sharp and

distant, the twin peaks of Mount Diablo. To the south

was Mount Tamalpais, and, yes, he was right, fifty

miles away, where the draughty winds of the Pacific

blew in the Golden Gate, the smoke of San Francisco

made a low-lying haze against the sky.

"I ain't seen so

much country all at once in many a day," he

thought aloud.

From Part II, Chapter

8 of Burning Daylight, serialized in The New York Herald, June-August,

1910.

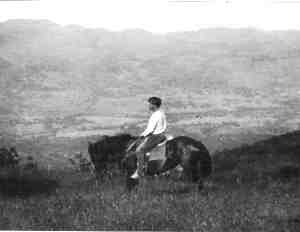

Spring view today from Lafferty

Ranch on Sonoma Mountain

toward Petaluma and beyond. Photograph by Scott Hess.

Robert Louis Stevenson's description of

ascending

a nearby Sonoma or Napa county ridge

A rough

smack of resin was in the air, and a crystal mountain

purity. It came pouring over these green slopes by

the oceanful. The woods sang aloud, and gave largely

of their healthful breath. Gladness seemed to inhabit

these upper zones, and we had left indifference

behind us in the valley. "I to the hills lift

mine eyes!" There are days in a life when thus

to climb out of the lowlands, seems like scaling

heaven.

From Chapter II, "First

Impressions of Silverado" of Silverado

Squatters by Robert Louis Stevenson

Henry David Thoreau

on our need to walk in nature

At present, in this

vicinity, the best part of the land is not

private property; the landscape is not owned,

and the walker enjoys comparative freedom.

But possibly the day will come when it will

be partitioned off into so-called pleasure-grounds,

in which a few will take a narrow and

exclusive pleasure only--when fences shall be

multiplied, and man-traps and other engines

invented to confine men to the PUBLIC road,

and walking over the surface of God's earth

shall be construed to mean trespassing on

some gentleman's grounds. To enjoy a thing

exclusively is commonly to exclude yourself

from the true enjoyment of it. Let us improve

our opportunities, then, before the evil days

come. At present, in this

vicinity, the best part of the land is not

private property; the landscape is not owned,

and the walker enjoys comparative freedom.

But possibly the day will come when it will

be partitioned off into so-called pleasure-grounds,

in which a few will take a narrow and

exclusive pleasure only--when fences shall be

multiplied, and man-traps and other engines

invented to confine men to the PUBLIC road,

and walking over the surface of God's earth

shall be construed to mean trespassing on

some gentleman's grounds. To enjoy a thing

exclusively is commonly to exclude yourself

from the true enjoyment of it. Let us improve

our opportunities, then, before the evil days

come.

From "Walking"

by Henry David Thoreau

So,

if there is any central and commanding

hilltop, it should be reserved for the public

use. Think of a mountaintop in the township,

even to the Indians a sacred place, only

accessible through private grounds. A temple,

as it were, which you cannot enter without

trespassing—nay, the temple itself

private property and standing in a man’s

cow-yard, for such is commonly the case. ...

That area should be left unappropriated for

modesty and reverence’s sake—if

only to suggest that the traveller who climbs

thither in a degree rises above himself, as

well as his native valley, and leaves some of

his grovelling habits behind.

I know it is a

mere figure of speech to talk about temples

nowadays, when men recognize none and

associate the word with heathenism. Most men,

it appears to me, do not care for Nature and

would sell their share in all her beauty for

as long as they may live for a stated and not

very large sum. ... It is for the very reason

that some do not care for these things that

we need to combine to protect all from the

vandalism of a few.

... I think that each town should have a

park, or rather a primitive forest, of five

hundred or a thousand acres, either in one

body or several—a common possession

forever, for instruction and recreation. ...

It frequently happens that what the city

prides itself on most is its park, those

acres which require to be the least altered

from their original condition.

From "Wild

Fruits"

by Henry David Thoreau

|

|

|

Editor's note: In the early

years of this century, writer Jack London owned and lived

on a ranch near Glen Ellen which extended to the top of

Sonoma Mountain. Much of this ranch now makes up

Editor's note: In the early

years of this century, writer Jack London owned and lived

on a ranch near Glen Ellen which extended to the top of

Sonoma Mountain. Much of this ranch now makes up

At present, in this

vicinity, the best part of the land is not

private property; the landscape is not owned,

and the walker enjoys comparative freedom.

But possibly the day will come when it will

be partitioned off into so-called pleasure-grounds,

in which a few will take a narrow and

exclusive pleasure only--when fences shall be

multiplied, and man-traps and other engines

invented to confine men to the PUBLIC road,

and walking over the surface of God's earth

shall be construed to mean trespassing on

some gentleman's grounds. To enjoy a thing

exclusively is commonly to exclude yourself

from the true enjoyment of it. Let us improve

our opportunities, then, before the evil days

come.

At present, in this

vicinity, the best part of the land is not

private property; the landscape is not owned,

and the walker enjoys comparative freedom.

But possibly the day will come when it will

be partitioned off into so-called pleasure-grounds,

in which a few will take a narrow and

exclusive pleasure only--when fences shall be

multiplied, and man-traps and other engines

invented to confine men to the PUBLIC road,

and walking over the surface of God's earth

shall be construed to mean trespassing on

some gentleman's grounds. To enjoy a thing

exclusively is commonly to exclude yourself

from the true enjoyment of it. Let us improve

our opportunities, then, before the evil days

come.